When the vast majority of people think of the NFL, their initial thoughts aren’t usually about European nobility. Most people typically associate professional football with the Super Bowl, brutal tackling, and screaming fans drinking Bud Light around a huge flat screen tv.

These are the images conjured up by most Americans regarding football. However, one team bears a logo many would consider very ‘non-football’ and, perhaps, non-American. That team is the Baltimore Ravens. Founded in 1996, the Ravens have won 2 super bowls and gave legendary linebacker Ray Lewis a professional home for 16 years. Your average everyday NFL fans are pretty familiar with those facts. But the majority of sports enthusiasts probably have no idea that their team bears the symbol of an oppressive Aristocratic family that ruled Maryland for almost 200 years.

This factoid may seem too odd to most people, especially Americans, that an American football team would portray a symbol of European nobility as their logo. And they’d be valid in their feelings. The United States, by all appearances, seems to be the very antithesis to the aristocracy. But America’s aristocratic roots run a lot deeper than most people realize. An in-depth look into the U.S’s early history reveals evidence of hereditary power, one similar to that of our friends across the pond, a power that extends its hand all the way to the White House. This article is a story of how America’s aristocracy began, thrived, ruled, and inevitably ended during an unprecedented wave of industry.

The Nicotine Machine

To begin our story, however, we have to talk about land first. During the colonial era, the land was everything. Throughout this period, Europeans found themselves in a mad harrowing scramble for new fertile lands all around the New World. The main reason for their heightened level of urgency was due to severe land shortage in Europe. Aristocrat’s land opportunities in the Old World were limited, and there was little hope of conquering parts of Asia.

Lord Baltimore, for example, was the Lord Proprietor of all Maryland. Meaning all the land within that designated area of colonial Maryland belonged to him. He could sell the land, give it away, or build a giant golf course for him and his friends. For the most part, however, Lord Baltimore’s treated their colony as a business investment.

Of course, the initial purpose for Maryland’s founding had more to do with religion than anything else. Initially, the settlement was started as a safe space for Catholics to worship (in 17th century England, Catholics were heavily discriminated against by the ever-growing Protestants). However, only 15 years after its birth, Maryland’s colony had a significantly larger Protestant population than the Catholics.

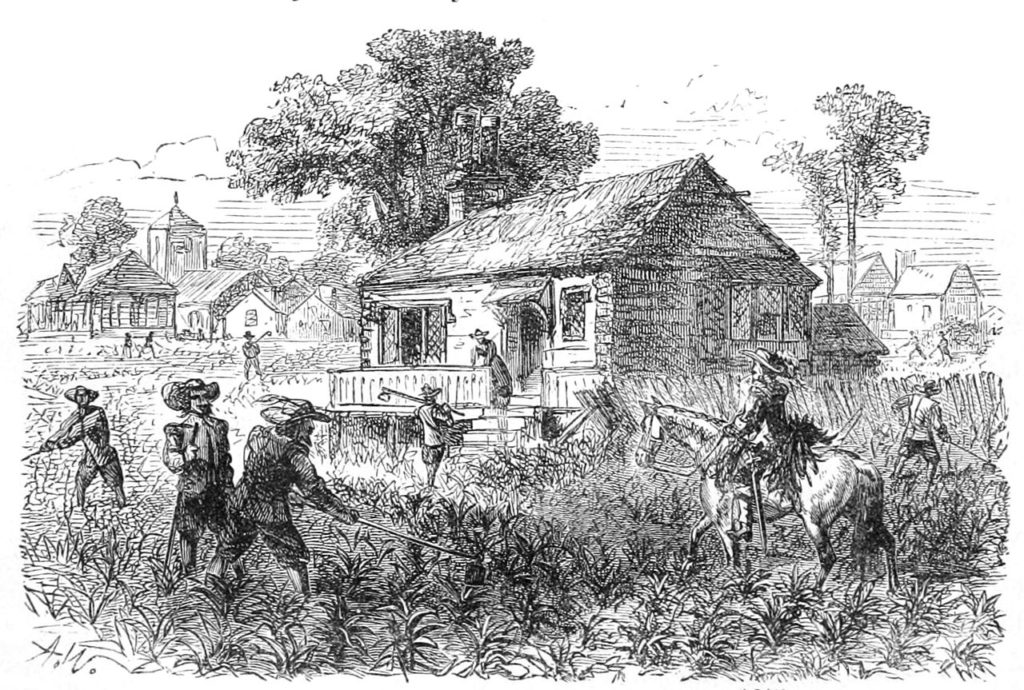

The reason for this disadvantageous population disparity for Catholics in Maryland was a desperate need for cheap labor, a workforce to help bolster the burgeoning cash crop of tobacco growing in sky-high demands back in the old world. The plant practically became its own currency, hence the term cash crop. And no colony benefited more from these profitable plants than Virginia. They were the primary catalyst behind the nicotine machine. It all began in 1611 when John Rolfe planted the first seeds of Caribbean tobacco in Jamestown. Little did Rolfe know, he had both literally and figuratively planted the seeds of America’s aristocracy.

The demand for fertile tobacco-growing lands was high, and the soil underneath Virginian colonists’ feet was of prime quality. But Virginia, being the first growers, had the advantage of a lengthy head start. I40 odd years later, the early jump on tobacco production bore its fruit. Many of the most powerful and influential founding fathers hailed from the colony of Virginia. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Patrick Henry, George Mason, George Wythe, and John Blair all participated in our United States’ founding.

Post founding, Virginia also provided the new nation with four of its first five presidents. Even the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C, is located on land donated by Virginia and Maryland. These facts indicate a clear, substantial socioeconomic and political dominance by the Virginia tobacco planters. But what was it that differentiated them from other states who had wealthy citizens like Massachusetts and New York?

To put it simply, Virginia planting families owned the land and the labor; therefore, they owned most of the economy. Due to Virginia’s aforementioned tobacco-friendly lands, most of their export was nicotine-based products; products that wielded sky-high demand back in Europe. As for the labor market, the plantations typically owned 20 to 100 slaves. In contrast, a smaller farm would usually top out at owning 2 to 5 slaves.

This broad difference in labor created a substantial gap between big plantations and their tenuous little brothers. We see an example of this dynamic occurring today. Companies like McDonald’s and Coca-Cola dominate the food and beverage industry when sized up to their much smaller mom-and-pop competitors. With similar dominance over a very undiversified economy, the opportunity for monopolization was rife for the southern plantation owners.

By the 1770s, Virginia had some of the wealthiest families in the 13 colonies. The planter families used their monetary power to divulge in influence over the newly formed United States. Of course, they were well-educated and intelligent men who brought much more than just money to the political table.

For example, George Washington was a brilliant tactician, and Thomas Jefferson a gifted and wise political philosopher. One fact does remain, however; these were not self-made men. They were what 21st century Americans would call “old money.” That’s not to say the Virginian founders were mere products of their family’s power and influence. They were much more than that. The Virginian founders made great everlasting accomplishments all on their own, without mommy and daddy having to hold their hand along the way.

However, their family’s hereditary influence undoubtedly helped them obtain and maintain their political control over the generations to come. An excellent example of Virginian political dynasties can be found in the Harrison family. Benjamin Harrison was the United States president for one 4 year term from 1889 – 1893, 20 plus years after Reconstruction. Benjamin’s grandfather, former president William Henry Harrison, had moved their family to Indiana years before Benjamin was born; Harrison’s ancestors arrived in Virginia back in the 1610s.

Over time the Harrison’s became a prominent planter family through their Berkeley Plantation. Although Benjamin Harrison did not grow up in Virginia, he certainly reaped the benefits of being a “Harrison.” Unfortunately for the wealthy southern planters, like the Harrison’s, their lead in the long-winded race towards dominance would be lost. The Civil War marked an end to slavery and to the extensive amount of free labor they enjoyed from it. Post reconstruction, the planters saw the world change and their way of life quickly regressing. This regression occurred due to what I like to call the Downton Abbey Effect.

The Downtown Abbey Effect

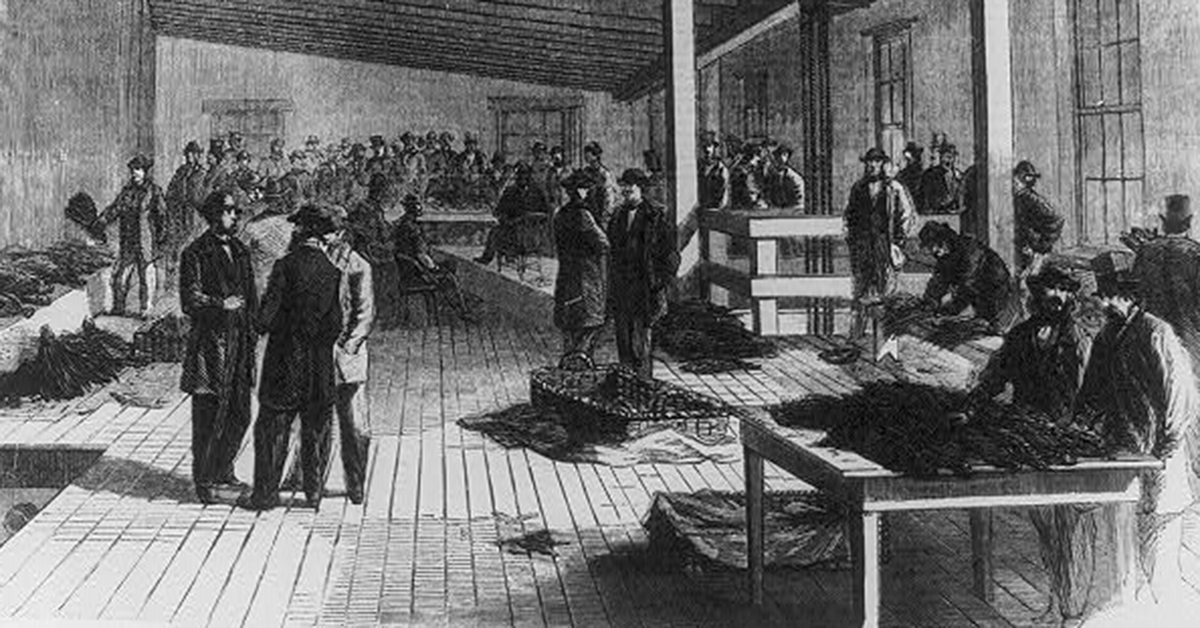

Historians note that the southern planters maintained power through the Reconstruction by way of sharecropping. Virtually a form of feudal like servitude, the sharecropping system allowed any southerner to rent and work a plot of land from a prospective landowner.

This new business model caused former planters to became landlords and, in turn, forced many slaves to become peasants. Overall, his system did little to change the racist power dynamic that had long permeated the south. As for the power dynamic regarding America as a whole, the Industrial Revolution, fat with innovative progress, finally tipped the scale.

No average joe wants to be ruled by very wealthy people who don’t do anything. Especially when there’s almost zero hope of ever climbing up the often greased class ladder, this natural human desire laid the foundation for the industrial age—the period of western civilization that slowly loosened the aristocracy’s long-held grip on humanity. Through technological innovation, a poor person could become ten times as wealthy as an aristocrat.

And many did. Inventors like Thomas Edison and businessmen like Andrew Carnegie created a whole new class of nobles, entrepreneurs. These upstart captains of industry didn’t need revenue-producing land inherited from their parents to succeed. They had to be creative and hardworking to attain their wealth. Although, it was a different kind of welsh than the Aristocrats had.

To sum it up, the Lords and Ladies still owned most of the land, but the entrepreneurs held most of the cash. However, it’s challenging to maintain land without money, allowing the rich entrepreneurs to swoop in and take it. We see all of these changes happening in Downton Abbey; the hit PBS show follows the Crawley family, a clan of wealthy English aristocrats trying to fit into this new world trying to get rid of them.

The show is all about change and how the old school Crawley’s react to it, sometimes gracefully and other times rather clumsily. Nevertheless, they do adapt to oncoming change, while many of their peers do not. The Crawley’s find creative ways of generating much-needed revenue to keep their archaic way of life going, like a car sputtering along with a near-empty tank of gas. Meanwhile, the other English nobles are brutally swept up in a tsunami of capitalism, with only empty titles and almost no cash to speak of.

The fictional show displays the effect that industry and innovation can have on the feudal system and why that style of governance is like almost any item one can buy at the dollar store: cheap and convenient at the moment, but not meant to last. That’s not to say the old aristocracy is entirely extinct (for example, in England, the ancient nobility still own around 60% of the land). But its position as the most powerful class on the caste went out the moment the light bulb switched on and filled the world with light.