By Karishma Joshi

Ashoka, the Ancient Indian Emperor

India has a rich history of royalty. Over the centuries, it has seen several dynasties headed by powerful kings and queens. Arguably one of the most prolific of these kings was King Ashoka, Emperor of the Mauryan Dynasty from 268 to 232 BCE.

Beautifully capturing Ashoka’s place in history, in ‘The Outline of History’, historian HG Wells writes “In the history of the world there have been thousands of kings and emperors who called themselves “their highnesses,” “their majesties”, “their exalted majesties”, and so on. They shone for a brief moment, and as quickly disappeared. But Ashoka shines and shines brightly like a bright star, even unto this day.

King Ashoka earned his glowing place in history because of the enormous change in his outlook after the Kalinga War, when he became a devout Buddhist. His beliefs made for a peaceful, prosperous kingdom with a ruler truly committed to the well-being of every individual in the kingdom.

Ashoka’s Early Years

Ashoka’s early years in no way predicted the illustrious ruler he would go on to become. He was born in 304BCE to Mauryan King, Bindusara, and Queen Devi Dharma, the daughter of a Brahmin priest. As a child, Ashoka quickly drew attention to himself thanks to his skills as a soldier and a scholar.

In early adulthood, King Bindusara appointed him as the governor of Avanti and sent him on a military campaign to fight an uprising in the Takshashila province, which he quickly suppressed. Jealous and insecure of his continuous successes, his siblings and half-brother convinced the King to send Ashoka into exile.

Following a violent uprising in the Ujjain province, Ashoka was called out of exile and sent to quell the rebellion; his military prowess ensured that he was quickly victorious. The Ujjain uprising was also significant to Ashoka’s religious journey, as after having sustained injuries in the battle, he was treated by Buddhist monks and nuns and introduced to the Buddhist way of life and thinking.

Seizing The Throne

After King Bindusura’s death, Ashoka’s half-brother Sushima succeeded him. However, his ineffectiveness led to Ashoka seizing power in 272 BC, after murdering all his brothers but Vithashoka, his youngest brother. According to some texts, he killed Sushima by pushing him into a burning coal pit, a violent act that was perhaps a harbinger to Ashoka’s early years of rule.

Ashoka The Fierce

Ashoka has been described in the literature as cruel, bad-tempered and violent. He was named ‘Chandaashoka’, which translates to ‘Ashoka the Fierce’ or ‘Ashoka the Terrible’.

According to some legends he commissioned the design of ‘Ashoka’s Hell’, a torture chamber, hidden inside a beautiful palace, filled with sadistic torture instruments, including vats of boiling copper to pour on prisoners.

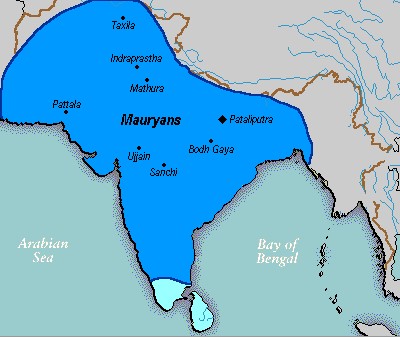

Ashoka also expanded the Mauryan Kingdom’s borders from modern-day Afghanistan to Assam to Baluchistan, seemingly unaffected by the trail of destruction he left behind.

The Kalinga War

Kalinga was located in present-day Orissa and had several large ports, a large navy and a population of skilled craftsmen, making it extremely attractive to the Mauryans. However, the first Mauryan effort to invade it, led by Chandragupta Maurya, Ashoka’s grandfather had failed. Ashoka was determined to turn this failure into victory and annex it to his kingdom.

He attacked Kalinga in 261 B.C. His military strength and weaponry skills once again prevailed and he won Kalinga. According to Buddhist literature as well as Ashoka’s own edicts, as he surveyed the battlefield, he was horrified by the bloodshed. The rock edict- Number 13, which is a primary source from Ashoka’s rule states:

“One hundred and fifty thousand were deported, one hundred thousand were killed and many more died (from other causes. After the Kalingas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods came to feel a strong inclination towards the Dharma, a love for the Dharma and for instruction in Dharma. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods or Priyadasi, feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kalingas.”

Even after he returned to Pataliputra, he was haunted by images of death on Kalinga’s battlefield. He suffered from a crisis of faith and it was at this point that Ashoka pledged never to wage war again. He instead became determined to live his life and rule his kingdom mindful of the principles of Buddhism, focusing on dharma-vijaya (a victory through religion) and ahimsa (non-violence). From Chandrashoka, Ashoka was transformed into Dhammashoka – Ashoka the Pious.

Ashoka The Pious

For the rest of his rule, Ashoka, in the words of HG Wells, “shone brightly like a bright star.” In 260BCE, he made Buddhism the state religion and framed his policies around the ten tenets of Buddhism which propagated kindness, non-violence, patience, honesty, simple life, and above all, a commitment to peace and harmony. It also required his subjects to love everyone, be tolerant, avoid selfishness and to be free of hatred of any kind.

Based on these tenets, King Ashoka created 14 edicts as rules for his subjects to follow. These edicts were inscribed on rock pillars or slabs of stone which were placed around his kingdom. They encouraged tolerance for all religions, a commitment to help the needy, medical care for all subjects, and respect for all living.

Above all, Dhamma – the collective term given to Ashoka’s rules of life – had to be revered and nothing could be better than gifting the Dhamma to others. He encouraged vegetarianism as a part of ahimsa. Slaughter and sacrifice of animals were forbidden. Ashoka made him accessible to his subjects at all times and they were encouraged to petition him in administrative matters which required redress. Monks had to tour the kingdom once in five years in order to spread Ashoka’s Dhamma. He dispatched missionaries, including his own daughter, Sanghmitra, and son, Mahendra, across his empire and abroad to teach the concept of Dhamma.

Ashoka’s welfare projects endeared him to his people and earned him a place as one of history’s most benevolent rulers. He built several hospitals, wells and gardens for growing medicinal herbs across his kingdom and made provisions for education for women and for the welfare of tribals.

Also, as a part of his active efforts to improve his kingdom, he established a successful political and civil system that divided his kingdom into provinces and appointed administrative and judicial officers who were overlooked by the King. He introduced legal reforms and created departments of finance, taxation, agriculture, trade, and commerce. To retain and strengthen his political control, he employed spies and reporters to keep him informed on tactical matters.

Legacy

Ashoka passed away in 232 BCE, after ruling his empire for about forty years. After his death, the Mauryan dynasty continued to thrive only for fifty more years, after which it disintegrated due to external invasions and internal revolts, caste conflicts, and the domination of the Brahmins.

Nevertheless, Ashoka has carried forward an immense legacy. He is lauded by Buddhists for highlighting a way to bring Buddhist principles into state power and paving the way to a better life for all subjects. Even today, the legacy of Ashoka’s proselytizing missionaries is seen in countries as far-flung as Cambodia and Thailand.

During his rule, he erected several stupas across the kingdom which, along with his edicts are important historical sources. One of his stupas, the Great Sanchi Stupa, has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNECSO.

Perhaps the most important symbol of Ashoka’s success which has been carried forward today is the Ashoka Pillar at Sarnath. It depicts four lions standing back to back in a circle. Today, it has been adopted as an emblem of modern India, in a way ensuring that Ashoka’s achievements and legacy will always remain in the world’s collective subconscious.