Who Was La Malinche?

The story of La Malinche is sadly shrouded through the eyes of others. La Malinche, otherwise known as Malintzin, and Doña Marina to the Spanish, did not write any records of her own life. Her legacy lives on through secondhand accounts, including briefly mentioned by Hernán Cortés. Which is sad because you know, she was more to him than just some daughter of an Aztec cacique (chief) he met. Both Mexica (Nahuatl) and Spanish accounts are as tricky and controversial as the last U.S. election results. And both sides see her as two totally different people.

Malitzen was born sometime around 1500, and here’s where it gets tricky. Many accounts of historical records say she was either kidnapped into slavery or given to slavers by her own mother at an early age. Either way, she ended up in a worse way with the natives of Tabasco. What we do know for sure is her life was changed in 1519 when the Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived.

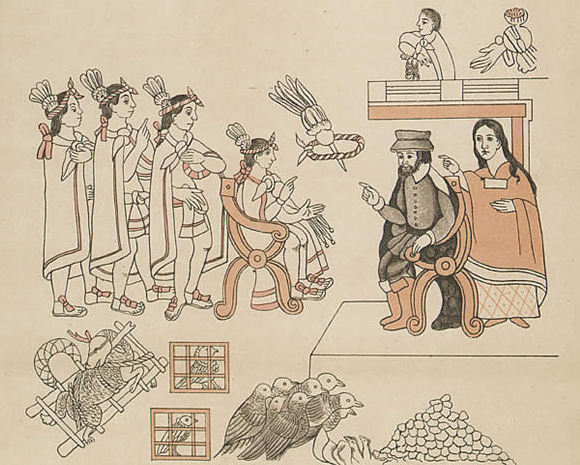

Cortés was given 20 women slaves when he arrived in the city of Pontonchan. Malitzen was one of those women. Cortés was the one who gave her the European name Marina and eventually “Doña” was added to distinguish herself as a respectable noblewoman. The -tzin was given to her as an honorific of the Aztecs after she gained prominence as an important woman.

Life as the Translator for Cortés

La Malinche to this day is given a bad rap, her name synonymous with betrayal and deceit. The term mostly used in Mexico, malinchista, is derived from her name. Why? Because she is seen as a traitor to the Meso-American people. When Cortés realized Malitzen could speak two major languages of the Yucatan Peninsula, he took her as his own personal slave. At first, she was paired with a Spanish priest who could also speak Yucatec but she quickly mastered Spanish so she could serve as Cortés’s sole interpreter.

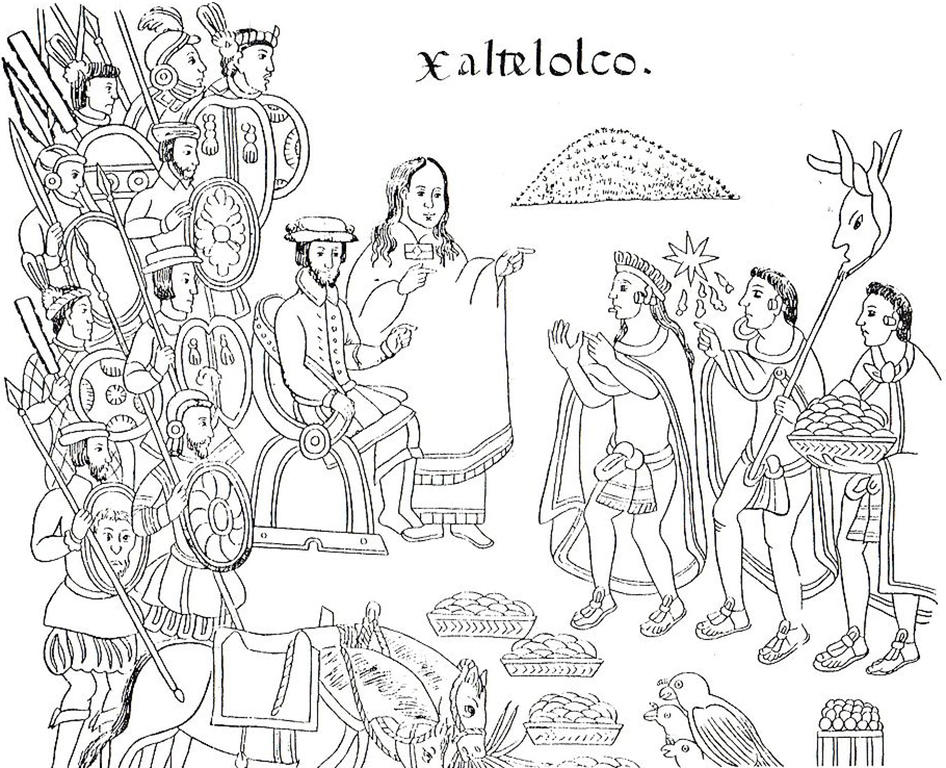

Throughout his conquest, Malitzen served as his right hand. She became so important in negotiations that even the Aztecs started to refer to Cortés as “Malitzen”, and Montezuma sent all of his correspondence to the Spanish to her. With Malitzen’s help, Cortés was able to make alliances with other tribes in the area who were tired of Aztec rule. Malitzen was also crucial in finding out plots to betray the Spanish, giving Cortés time to come up with a counterplan.

Through all of this and many believing she brought about the death of the Aztec Empire, she was still a slave. It was either obey her master or die. Since she left no written account, we will never truly know her motives. After the fall of the Aztec Empire, Malitzen continued to live with Cortés and she bore him a son named Martín in 1522. Like many other aspects of her life, we do not know if she willingly became his mistress or if he forced himself upon her.

From Slave to Nobility…Again

In 1524 her life changed again after she served as interpreter once again to quell a rebellion in modern-day Honduras. That same year, Malitzen married Juan Jaramillo, one of Cortés’s captains. The marriage made her a free woman, which is interesting since it is said Cortés himself arranged the marriage.

Rumor has it, it was because he needed to get her out of his house before his actual wife arrived from Spain. She was now a member of the Spanish nobility with all the rights and honors in both Mexico and Spain.

In 1526, she gave birth to their first daughter, Maria. Her new marriage and the birth of her children meant they would not only be seen as Spanish nobility, but also she became the “mother of the mestizo”, a new mixed-race generation between the Spanish and Aztecs.

The Death of La Malinche

Accounts from her children put La Malinche’s death somewhere between 1551 and 1552. Due to the mystery of her actual birth date, possibly no later than 1505, we do not have an actual age for her death. However, if you Google it Google will tell you she died in 1529 due to smallpox. Wrong-o. I mean I don’t know who are we gonna believe here her children or Google? You tell me.

Sadly, we will never know why she did what she did. But it is up to you, armed with the facts, to see her either as a traitor or as a victim of her own people and trying to survive the Spanish Conquest.

Resources:

Garsd, Jasmine. “Despite Similarities, Pocahontas Gets Love, Malinche Gets Hate. Why?” NPR, NPR, 25 Nov. 2015, www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2015/11/25/457256340/despite-similarities-pocahontas-gets-love-malinche-gets-hate-why.

“Life Story: Malitzen (La Malinche).” Women & the American Story, 10 Nov. 2020, wams.nyhistory.org/early-encounters/spanish-colonies/malitzen/.

“Malinche: Indian Princess or Slavish Whore?: AHA.” Malinche: Indian Princess or Slavish Whore? | AHA, www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/teaching-resources-for-historians/teaching-and-learning-in-the-digital-age/the-history-of-the-americas/the-conquest-of-mexico/narrative-overviews/malinche-indian-princess-or-slavish-whore.

Mohammed, Farah. “Who Was La Malinche?” JSTOR Daily, 1 Mar. 2019, daily.jstor.org/who-was-la-malinche/.