Netflix’s hit alternative-Regency series, Bridgerton, may well be set around the love lives of the aristocratic Bridgerton family. However, the show’s real star is the ever-present, mysterious Lady Whistledown, the all-knowing author of a popular scandal sheet that makes — and breaks — reputations.

It is Lady Whistledown who raises — and casts down — the season’s debutantes with her waspish observations, leaving society in awe of the mysterious woman who “knows everything about everyone.”

Apart from the royals, the eponymous Bridgerton family and the majority of the cast of Bridgerton are fictitious. But while there never was a real “Lady Whistledown”, there is a historical model for her character; a real-life “lady that knows everything” and author of her own scandal sheet, The Female Tatler. That lady’s name was Mrs Crackenthorpe.

The Rise of the Scandal Sheet

Eighteenth-century London was the birthplace of the scandal sheets; “newspapers” or magazines dedicated to spreading salacious society gossip. These early tabloids arose at a time when society was shifting.

The early eighteenth century was a boom time for the free press. In 1695, the abolition of the 1662 Licensing Act removed limitations on the press, allowing the reporting of news — and gossip — to flourish. By 1712, there were 20 new papers in London alone. With so many news sheets, there was a real competition to grab the attention of the public. Then, as now, celebrity gossip was the way to hook people — and London society provided plenty of juicy gossip and scandal about the wealthy and aristocratic to bait readers and reel them in.

Newspapers such as Town and Country began to include “tete a tete” columns reporting on crime, infidelity, and gossip about royalty — and the growing population of London couldn’t get enough. So popular were the details of the lives of the rich and famous that dedicated “scandal sheets” began to grow up, where every page was packed with writing — and pictures — detailing the indiscretions of society’s upper echelons.

Popular early eighteenth-century scandal sheets included The Flying Post, The British Apollo, and The Tatler, which is still going strong. Most aimed at both men and women. But in 1709, a unique sheet arose. Called, The Female Tatler, it was published on the days The Tatler was not (Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays ) and was aimed exclusively at women. Its initial author was also a woman.

Mrs Crackenthorpe — The Eighteenth-Century Lady Whisteldown

Mrs Crackenthorpe echoes much of Lady Whisteldown’s style — and subject matter — uncannily. Although not solely preoccupied with the lives and loves of the season’s debutantes, Mrs Crackenthorpe was just as satirically scathing, aiming her sharply observed, innuendo-laden “feminine wit” at various society figures, “notable for scandal and scurrility”.

However, unlike Lady Whistledown, Mrs Crackenthorpe did not use her victims’ real names. Instead— as was the custom of all scandal sheets of the time — she used pseudonyms. These fictional names epitomized common characteristics of the people concerned, so readers could easily identify them — and the author avoids a libel case.

So it was a “Madam Slender Sence” who was described in one edition as having “lately fallen ill of a swelling she received by a slip the last ball night” after an implied alliance with a French dancing master. Mrs Crackenthorpe cites her source for this information as “Mrs Manlove, who generally searches into the bottom of such affairs” and who “solemnly protests she saw them go up one pair of stairs together. What they did there, she can’t tell, but the lady has been ailing ever since.”

Mrs Crackenthorpe was also fond of borrowing the names of characters from the popular stage who “suited the odious dispositions” of the persons concerned. One was “Lady Politick Wou’d be”, a character from Ben Johnson’s Volpone, who she used to epitomize a well-known society hypochondriac.

Mrs Crackenthorpe claimed her gossip was morally educational and that it was her duty to report and ridicule the “unaccountable whims and extravagant follies” of “the better sort”. Her reason for this was so that the “inferior classes” who would “imitate them in their habits of mind as well as body” could be taught to behave better. “A seasoned banter has often had a reclaiming effect,” concluded Mrs Crackenthorpe’s dubious justification.

Can the Real Mrs Crackenthorpe please step forward?

“Crackenthorpe”, however, was no more real a name than the names of The Female Tatler’s subjects. As with Lady Whistledown, no one knew who the scandal sheets mysterious author was — although there was some debate.

Some suggested that Mrs Crackenthorpe was Thomas Baker, a lawyer and minor dramatist who wrote several comic plays before disappearing off the London scene. However, a second, more likely candidate was the author, playwright, and political pamphleteer Delarivier “Delia” Manley.

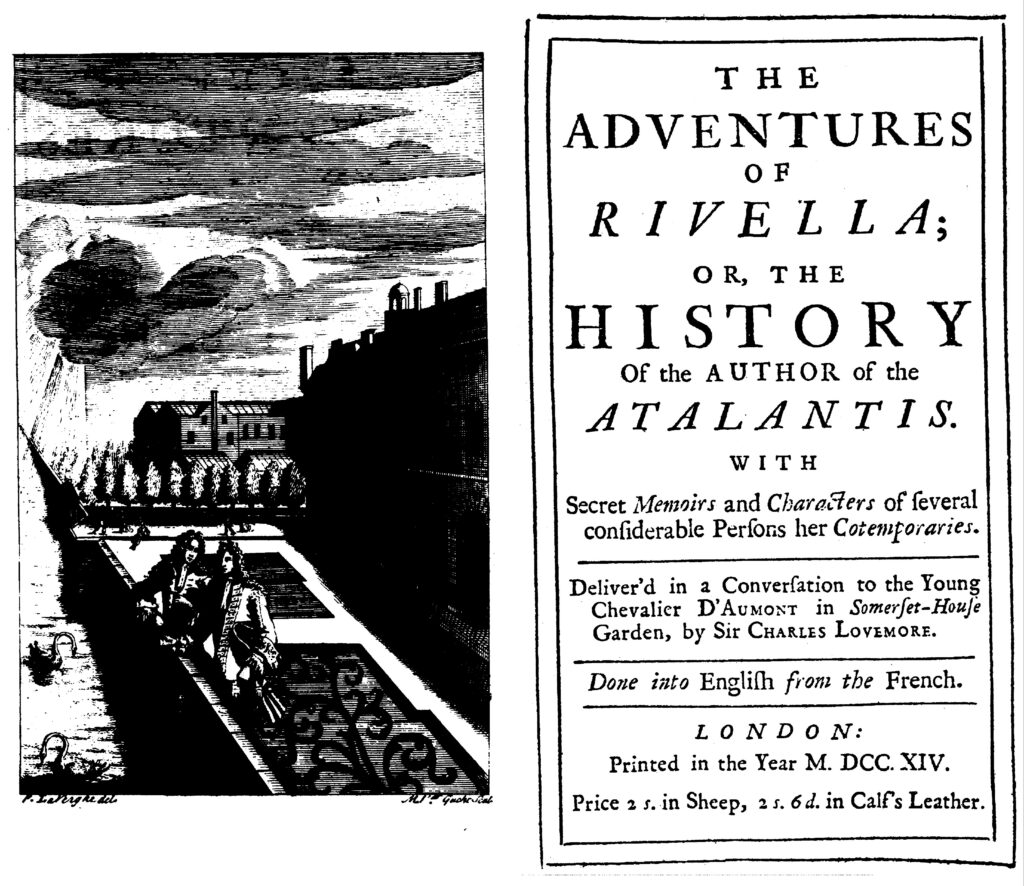

Manley was the author of The New Atalantis, a scandalous, political novel published in two volumes in 1709. Many of the book’s themes were uncannily echoed in The Female Tatler — as were characters who closely resembled members of Manley’s own family. The content of The New Atalantis so badly discredited several Liberal and Tory MPs that Manley was arrested.

Manley’s arrest curiously corresponds with a significant event in the life of The Female Tatler — the sudden resignation of Mrs Crackenthorpe after 51 editions. But while the case against Manley was dropped — probably to spare the politicians involved further scandal — Mrs Crackenthorpe never returned. She was replaced by the anonymous but less successful “Society of Ladies”. The Female Tatler did not long survive its change of author and, after a steady decline, folded after just a year.

Sources:

Anderson, Paul Bunyan. “La Bruyère and Mrs. Crackenthorpe’s Female Tatler.” PMLA 52, no. 1 (1937): 100-03. Accessed March 12, 2021. doi:10.2307/458700.

Anderson, Paul Bunyan. “The History and Authorship of Mrs. Crackenthorpe’s “Female Tatler“.” Modern Philology28, no. 3 (1931): 354-60. Accessed March 12, 2021.

Archer, Zoe, Scandal: Gossip Rags, 18th Century Style. Unusual Historicals,

Bilyeau, Nancy, Bridgerton, Lady Whistledown, and the Secret History of High-Society Gossip, Town & Country.

Gardner, Victoria, Liberty, Licence and Leveson, History Today (Published in History Today Volume 63 Issue 2 February 2013

Overdeep, Meghan, History’s Real-Life Lady Whistledown Revealed, Southern Living

Taylor, Elise, Bridgerton: The Real-Life Lady Whistledowns of Regency-Era England. Vogue

Issuing Her Own: The Female Tatler