“Just as women’s bodies are softer than men’s, so their understanding is sharper.”

― Christine de Pizan

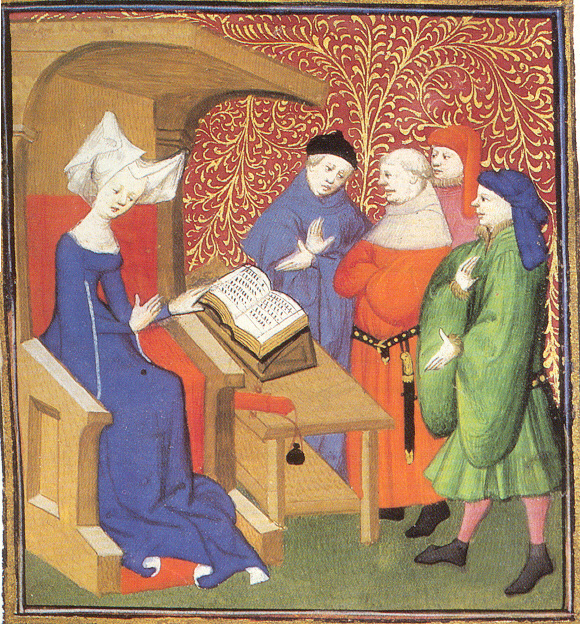

You might be surprised to know that the quote you just read was written in the middle ages by poet Christine De Pizan. In our modern times, she is seen as a progressive thinker who gets their point across via poetry, like Amanda Gorman. And Amanda has a medieval parallel, the feminist (as feminist as one can be in the middle ages) poet Christine de Pizan (1364-1430).

Christine wrote The Tale of the Rose as a polemic attacking the perceived misogyny and sexism in De Meuns’s book, which portrayed the female characters as aggressive one-dimensional seducers.

I’d Like to Thank My Sponsor

The middle ages were a difficult time for women, especially theologically. In other words, the consensus of the day was that women were spiritually inferior to men, mainly that women were less virtuous than men. That was one topic Christine took up to combat for what she perceived as misogynistic thinking by the philosophers of medieval Europe.

Being born to a successful intellectual father, Christine grew up around books and intellect from an early age. Her father was not rich by any means but passed down to her several royal connections he had accumulated after years serving in the court of French King Charles V.

Even after she lost her husband, a much bigger problem back in 14th century central Europe, Christine used those connections to start a business.

By that point, Christine and her husband had already popped out 3 children, and due to his death, Christine was left to support them. In a totally badass move, Christine began selling the only asset she could, her poetry. In those days, aristocrats and royals paid good money for art.

Many of them became sponsors for local artists that they felt could create things that made them look good (like a painter painting them winning a battle or wearing a pretty dress) or put their name on something the people would love. Which also made them good. Similar to how the wealthy classes of today put their names on buildings and art exhibits.

In Christine’s case, the wealthy hired her as a poet to write the Medieval equivalent of a cheesy RomCom, otherwise known as a love ballad.

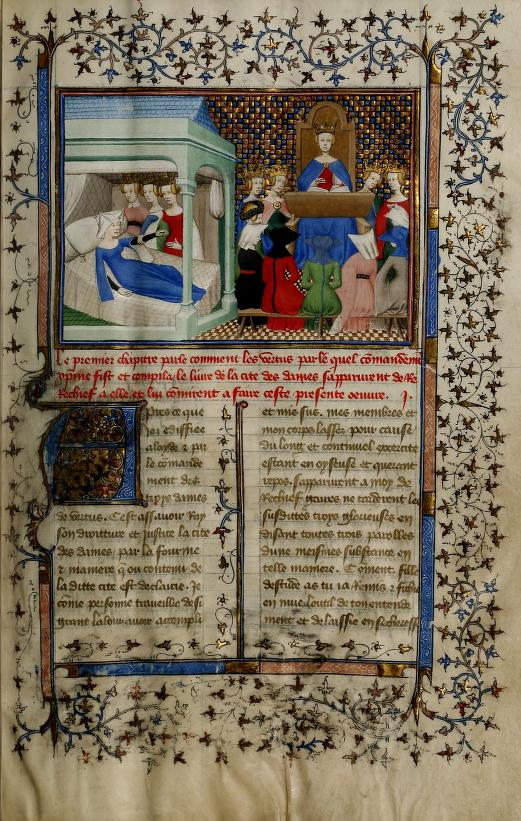

Christine’s first major royal sponsor was the French queen Isabeau, who had to deal with a mentally ill husband and often had to govern in his place during his frequent episodes. To give herself credit for governing the royal court in her husband’s absence, Isabeau commissioned Christine to write a piece of prose praising her deeds to a people who still viewed women as less virtuous than men. With virtue being a sought out quality in a leader.

Christine, who still needs to provide for children, gladly took the job. In her work for the powerful queen, Christine wrote praises such as:

“High, excellent crowned Queen of France, very redoubtable princess, powerful lady, born at a lucky hour.”

In the bigger picture, the works Christine published were meant to argue for the virtues of a woman in a world that assumed they had none. Although the dedication to Queen Isabeau was Christine’s first feminist work, it was The Tale of the Rose that became her flagship feminist work.

War of the Roses

Christine wrote the book in response to another well-known writer’s book, Jean De Meuns’s Romance of the Rose, a bestseller in medieval times. Christine wrote The Tale of the Rose as a polemic attacking the perceived misogyny and sexism in De Meuns’s book, which portrayed the female characters as aggressive one-dimensional seducers.

This passage here is a great line:

“Those who plead their cause in the absence of an opponent can invent to their heart’s content, can pontificate without taking into account the opposite point of view and keep the best arguments for themselves, for aggressors are always quick to attack those who have no means of defense.”

By 2021 standards, Jean De Meuns has been roasted and toasted. As you can see, Christine did not mince words in her polemics.

Of course, alongside her ‘ahead of her time’ feminist beliefs, Christine had some rather odd and outdated views (by 2021 standards). For example, she believed the French people descended from Trojans for some reason. And, to the chagrin of many modern feminists who praise Christine, she still felt that women needed to stay in their place, meaning that they should remain in their roles in society as a good medieval woman should.

As I said, she was as feminist as you could get in the middle ages. She also advocated hereditary monarchy, which makes sense considering who her bosses were. Throwing them a politically lifting bone now and then kept the money rolling in.

The Legacy

The middle ages, for merchants, we’re all about the elites and figuring out ways to get a hold of some of their money. As a whole, however, Christine stood up for an entire half of the population who genuinely did not have a voice. Historians consider her the first female poet and public intellectual in medieval history, making Christine a significant trailblazer for feminism, despite her medieval beliefs.

Sources:

Lee, C. (2015, February 25). World-Changing Women: Christine de Pizan [Blog Post]. Retrieved from https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/world-changing-women-christine-de-pizan

Margolis, N. (1986). Christine De Pizan: The Poetess as Historian. Journal of the History of Ideas, 47(3), 361-375. doi:10.2307/2709658

Palumbo, A (2020, March 12). This Single Working Mom Was Europe’s First Professional Woman Writer [Blog Post]. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/single-working-mom-europe-first-professional-woman-writer

(1995). Reclaiming Rhetorica: Women and in the Rhetorical Tradition. University of Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved from https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/christine_de_pisan