With the 2020 presidential election looming, now is a good time to remember the struggle women faced in earning the right to vote in the U.S. and the U.K. While the fight for women’s rights is still very real today, one hundred years ago the battle for a woman’s right to vote was sometimes fierce because our fellow sisters grew tired of living under archaic rules. For these women suffragists, it was a struggle marred by violence, with the Night of Terror perhaps being the most devastating example.

On the night of November 14, 1917, 33 women gathered outside the Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton, Virginia. The women had been arrested a few days earlier after protesting at the White House, where Woodrow Wilson was President. Holding banners and placards, the women called on Wilson to support a federal amendment that would give all women in the U.S. the right to vote. But Wilson was unsympathetic and as America entered into World War I in April 1917, he became even less so, and in a June letter to his daughter he wrote that the suffragists “seem bent on making their cause as obnoxious as possible.”

Tensions continued to build until that terrible November night when the women demanded to be treated as political prisoners. What they got instead were surly prison guards who’d been ordered by superintendent William H. Whittaker to teach the women a lesson. The guards threw them into dank, filthy cells and the beatings began. Some were shackled to the ceilings and forced to stand all night; one woman was slammed onto the iron arm of a bench twice, another woman had her head smashed into an iron bed and lost consciousness.

But for many women, brutality merely strengthened their resolve and this movement is known for some truly remarkable suffragettes in the United Kingdom and the United States. These sisters fought the long and often bloody battle that led to the 19th Amendment that gave millions of American women the right to vote in 1920, while our British sisters earned the right to vote in 1918 when Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act in 1918 and The Equal Franchise Act in 1928.

6 Incredible Suffragists

For the fierce women warriors below, the fight began in the 18th century.

- Sojourner Truth

- Emily Davison

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton

- Emmeline Pankhurst

- Ida B. Wells

- Constance Lytton

1. Sojourner Truth c. 1797?—1883

Born into slavery in upstate New York, Isabella (later Van Wagener) became the first known African-American suffragette. Upon emancipation in 1823, Sojourner became an itinerant preacher and reformer who supported herself with menial jobs. An outspoken women’s rights activist, she traveled throughout the eastern United States, attending conventions dedicated to these rights.

A powerful and magnetic person, Sojourner Truth captivated audiences with her unique oratory, even winning over a few skeptics in the process. In 1853, the author Olive Gilbert was inspired to write the Narrative of Sojourner Truth, and the book was a lifeline for Sojourner, who sold copies to earn money. She became friends with Harriet Beecher Stowe, another famed abolitionist, and writer, who came to call her the “Lybian Sibyl,” in a story that appeared in The Atlantic in 1863.

During an electrifying speech at the Akron, Ohio, women’s convention in 1851, she delivered her now-famous “Ain’t I A Woman” speech. There’s currently some controversy surrounding this speech because it’s written in the dialect that was common among slaves of the south while Sojourner grew up in Dutch-speaking New York. Whatever the case, the speech is moving and powerful:

“Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ‘twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man — when I could get it — and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? [audience member whispers ‘intellect’]. That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negroes’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men,’ ‘cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain’t got nothing more to say.”

This powerful speech cemented her place in American history as a champion for women’s rights and the right to vote, and she was welcomed into the White House by President Abraham Lincoln in 1864. Later that year, the National Freedman’s Association Relief Association appointed her as “counselor to the freed people at Freedman’s Village, in Arlington Heights, Virginia. She was an unflinching advocate for the rights of Black men and women to vote, and in 1875 Sojourner returned to Battle Creek, Michigan, where she’d lived in years past, and continued to lecture until her death in 1883.

2. Emily Davison October 11, 1872—June 8, 1913

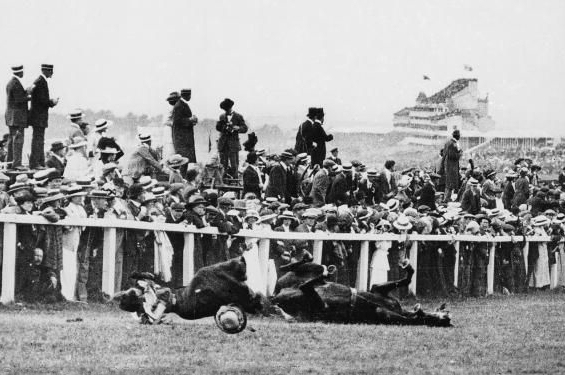

Born in London, England, Emily Davison paid the ultimate price for fighting for the right to vote when she stepped in front of the king’s horse during the Epsom Derby. Questions have been raised in the decades since over her controversial death, with some claiming she was a reckless anarchist and others calling her a brave martyr for the cause.

Her death was captured on film, which was in its infancy during this time. Filmed by three newsreel cameras, it led some to claim Davison was trying to pull down Anmer, the royal racehorse. Despite these sophisticated innovations, her intentions still remain unclear, but some historians have noted Davison and other suffragettes were seen “practising” at attempting to grab horses in a park near her mother’s home and drawing lots to determine who should attend the race.

And Davison was known for her fearlessness and militancy in the British suffragette movement. She was notably intelligent, attending Kensington Prep School and taking classes at Oxford University and Royal Holloway College. Unfortunately, she didn’t earn an official degree at either university because women were not allowed to do so at this time.

Not long after, she became a teacher and found herself becoming increasingly socially and politically active, joining the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), which was founded by another prominent suffragette, Emeline Pankhurst.

Davison was not afraid to act out when needed and was arrested and imprisoned on numerous occasions, having given up teaching in 1909 to dedicate to the women’s suffrage movement.

Her incarceration that same year at Manchester’s Strangeways Prison may be the most notable. Here, she embarked on a hunger strike, something that many imprisoned suffragists did to protest the government’s refusal to denote them as political prisoners. At one point, she barricaded herself inside her cell for a time, but guards responded to that by flooding it with water. She would later write “I had to hold on like grim death. The power of the water seemed terrific, and it was cold as ice.”

1912 saw her serving another stint in incarceration, this time at Holloway Prison. Suffragettes were brutally treated at this prison, and those who went on hunger strikes were regularly force-fed. Davison thought she might be able to put an end to this cruel treatment by jumping off a prison balcony.

“The idea in my mind was that one big tragedy may save many others,” Social Research reports.

This unflinching bravery in the face of adversity shows how far Davison was willing to go, and on that fateful day in June 1913, carrying two suffragette flags, she ducked under the railing at the raceway and stood on the track. Holding her hands up as the horse bore down on her, King George V and Queen Mary watched the horrifying spectacle unfold.

It almost seems like Davison’s intentions were suicidal, but there’s confusion surrounding this because she bought a round-trip train ticket for the way home after the event. Thousands of supporters of the Votes for Women movement attended her funeral, and her body was laid to rest in Morpeth, Northumberland. Her headstone fittingly reads “Deeds Not Words” a popular motto among suffragettes.

3. Elizabeth Cady Stanton November 12, 1815 — October 26, 1902

Born to an affluent family in upstate New York, Stanton was no bourgeois snob. Surrounded by numerous reform movements from the very beginning, Stanton became an ardent abolitionist and advocate for women’s rights. After marrying fellow abolitionist Henry Brewster Stanton in1840, the couple traveled to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, England. Unfortunately, the Stantons have turned away.

The reason?

Female delegates were not allowed at the convention. And that meant Elizabeth Cady Stanton fitted another cause under her belt: Equal rights for women. She began to believe that women needed to seek equality for themselves before they could advocate for others, and in the summer of 1848, she met with abolitionist and temperance advocate Lucretia Mott and a group of other reformers. Together, they organized the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York.

The conference was attended by 240 women and men who were there to discuss what Stanton and Mott called “the social, civil and religious condition and rights of women.” That led some of the delegates — 68 women and 32 men to sign the “Declaration of Sentiments,” which was modeled after the Declaration of Independence. Like that famous document, it declared women were equal to men, with the “inalienable right to the elective franchise.” And thus, the Seneca Falls Convention was the birthplace of the suffrage movement.

4. Emmeline Pankhurst July 15, 1858 — June 14, 1928

Born in Manchester, England, Emmeline Goulden was the eldest daughter among 10 children. Hers was a family of activists; both parents were dedicated abolitionists and supporters of women’s suffrage. It was her mom, in fact, who took 14-year-old Emmeline to her first women’s suffrage meeting.

But despite their support of women’s suffrage, Emmeline’s parents put their sons’ education and advancement first and this became a source of frustration for her. She furthered her own education by studying in Paris and later returned to Manchester, where she met and married Dr. Richard Pankhurst in 1878. Although Richard was 24 years older than Emmeline, he supported many radical causes, including equal rights for women and the right to vote.

It wasn’t long before she was a busy mother, caring for three daughters — Adela, Christabel, and Sylvia, and two sons — Frank (who died in childhood) and Harry. Even so, Emmeline continued to be involved in politics, campaigning for her husband as he ran for Parliament. While his attempts were ultimately unsuccessful, she continued hosting political gatherings at the family home. All along the way, Richard encouraged her until his death in 1898.

Although his death was a heavy and impoverishing blow, Emmeline managed to pull herself together, forming the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Eventually, Pankhurst’s daughter Christabel joined and over time, the group became increasingly militant, confronting politicians and holding rallies. That led to arrests and imprisonment, with Pankhurst herself being sent to prison in 1908.

Pankhurst initially encouraged WSPU members to keep their demonstrations lawful, especially when legislation regarding women’s suffrage was on the horizon, but group members grew frustrated after two Conciliation Bills that included women’s suffrage failed in 1910 and 1911. Now the group’s protests escalated and anarchy followed in 1913. By now, members were breaking windows, committing arson, and defacing public artworks. That was followed by arrests and throughout this time period, the women who were incarcerated began hunger strikes.

But after a bomb exploded at an unoccupied home that was being built for chancellor of the exchequer David Lloyd George, Pankhurst was sentenced to three years for inciting crime. She was subsequently released after launching a hunger strike.

With the advent of WWI, Pankhurst called for an end to the militancy and the demonstrations and the government released all WSPU prisoners. Pankhurst encouraged her fellow sisters-in-arms to join the war effort by filling jobs so that men could join the war.

Those contributions convinced the government to grant women limited voting rights in 1918, However, it took all the way until 1928 and the passage of the Equal Franchise Act for women to fully receive the right to vote.

By the time of her death at age 69 in 1928, Pankhurst was a force to reckon with, having fought bravely to advance the rights of women all her life.

5. Ida B. Wells July 16, 1862 — March 25, 1931

Born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Ida was the oldest daughter of James and Lizzie Wells. When she was just a few months old, President Lincoln’s famous Emancipation Proclamation freed all slaves who had been held captive by the Confederacy.

But the Wells family was constantly beset by racism and hampered by discriminatory laws and practices. Nevertheless, the young girl’s parents remained very active in the Republican Party as the Reconstruction period held sway after the end of the Civil War. Her father James founded Shaw University, which later became Rust College, and this is where Ida received much of her schooling.

Her young life was marred by tragedy, however, after a devastating outbreak of Yellow Fever killed James and Lizzie, along with one of her siblings. Now she was left to care for her remaining brothers and sisters. This was indeed a setback, but Ida was more than equal to it, convincing a local school administrator that she was 18, and that resulted in her becoming a teacher.

In 1882 Ida and her sisters moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where they lived with an aunt. Meanwhile, her brothers found work as carpenter apprentices, and Ida resumed her studies at Fisk University in Nashville.

It wasn’t long before Wells began her journalism career, writing on politics and race issues for a number of Black newspapers and periodicals under the pen name “Iola.” Over time, she became the owner of The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight and, later on, another newspaper, the Free Speech.

But a shocking act of racism that was unfortunately typical of the day galvanized her. She’d bought a first-class train ticket but crew members on the train forced her to move to the car reserved for African-Americans. Outraged, she refused on principle. Wells was definitely not a woman to go down without a fight and while being forcibly removed she bit one of the men on the hand. She later sued the railroad and won a $500 settlement but the decision was later overturned by Tennessee’s Supreme Court.

This injustice infuriated her further and her journalism career was launched. While she was busy as a journalist and publisher, she also held a job as a teacher in a segregated public school in Memphis. But the conditions Black children faced in these schools upset her and Wells became very vocal in criticizing the situation. That eventually led her to be fired in 1891 and she set her sights on championing a new cause after the murder of a friend and his two business associates.

The men — Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart, who were all African-American, had set up a grocery store, which drew customers away from a nearby white-owned grocery store. That didn’t sit well with the white, racist owner of the store and it led to clashes with the three men from time to time. The tensions came to a head one night when Moss and his friends, who were guarding their store, shot several whites who were vandalizing it. Moss, McDowell, and Stewart were arrested but never given the chance to defend themselves. Instead, an angry mob dragged them out of their cells and lynched the men.

Wells was fearless in the face of such atrocities, writing articles decrying the lynching of her friend and the cruel murders of other African-Americans and risking her own life during this time of heightened tensions by traveling across the south, researching other lynching incidents.

And white people treated her mercilessly, even at one point breaking into her office and destroying all of her equipment. Wells was in New York City at the time and she was warned that she would be killed if she ever returned to Memphis. Undaunted in the face of terror, she continued writing on lynchings and in 1893, published A Red Record, her own personal examination of lynchings in America.

The issue of women’s suffrage was never far from her heart, but sadly, she was faced with racism even here. In March 1913, she prepared to join the suffrage parade during Woodrow Wilson’s inaugural celebration. But organizers asked her to stay out of the procession because some white suffragists objected to walking alongside Black people. Cases like this were fairly rare, fortunately, and most early activists supported racial equality.

But by the beginning of the 20th century, many middle-class whites embraced the suffragists because they believed that by emancipating their own women they were guaranteeing white supremacy by invalidating the Black vote.

Wells, fortunately, was undeterred and joined the march anyway. This brave woman spent the rest of her life fighting for civil rights, and after marrying Ferdinand Barnett in 1895, she and her husband co-founded, along with W.E.B. Dubois and several others, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

This impressive woman left behind a remarkable legacy and passed away in 1931. She was forced to deal with prejudice in one form or another, all her life but remained steadfast in rejecting it, notably saying at one point:

“I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap.”

6. Constance Lytton February 12, 1869 — May 2, 1923

Born to a life of privilege as the daughter of Viceroy Robert Bulwer-Lytton, Constance spent her life as a child in India, along with her two brothers and four sisters. When the family returned to England Constance became involved in charity work. As part of her charitable work with girls in the fashion industry, she met suffragettes who’d been imprisoned. That led her to become a suffragette herself alongside her sister Betty.

It wasn’t long before she was giving speeches all over the country, and she was arrested in a number of places. But the one arrest that perhaps affected her the most happened in Liverpool in 1910. She was using the name Jane Wharton at the time because the name Jane reminded her of Joan of Arc. Constance was force-fed eight times during her imprisonment and it’s said that she never completely recovered from this.

She preferred to be treated like an ordinary person and detested it when she was given preference because of her status as the daughter of an Earl. But the stress of being arrested numerous times took a toll on her health. Even so, she was able to write on her experiences of being imprisoned as a suffragette. Her book Prisons and Prisoners perhaps being the most notable example. After women gained the right to vote, Constance moved in with her mother. But her health, worsened by the conditions in prison, continued to decline and in a letter to her aunt, Theresa Earle said that she was ready to accept death.

“If it should happen… I am happy to die. If, as many people believe, we step into a higher life, but are again with loved companions who have died before, then it will be very good,” she wrote. “Death to me is like a gentle lover …I am so tired of life, I should like to be taken in his sheltering arms and have an end… I have long hoped to die, and since I’ve seen this possible road, I have felt most wonderfully happy. Of late years I have seen and felt much of the sad side of death — the separation from those we love. Now I see the joyful side — the release from bodily ills — and it is restful beyond all words.”

These are a mere few of the women who gave their all — in the United States and the United Kingdom so that we can vote, something that many of us take for granted — and shouldn’t. Because now, more than ever, our very lives may depend on it.

As Election Day approaches, perhaps we should keep this in mind.

Sources:

History.com

https://www.history.com/news/night-terror-brutality-suffragists-19th-amendment

FindMyPast.com

https://www.findmypast.co.uk/blog/history/famous-suffragettes

History.com

https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/women-who-fought-for-the-vote-1

Turning Point Suffragist Memorial

https://suffragistmemorial.org/african-american-women-leaders-in-the-suffrage-movement/

Time.com

https://time.com/5542892/kitty-marion-suffrage-birth-control/

History.com

https://www.history.com/news/night-terror-brutality-suffragists-19th-amendment

Parliament UK

https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/overview/thevote/

Documenting the American South

https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/truth50/truth50.html

The Atlantic

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1863/04/sojourner-truth-the-libyan-sibyl/308775/

National Park Service

https://www.nps.gov/articles/sojourner-truth.htm

Biography.com

https://www.biography.com/activist/emily-davison

The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/may/26/emily-davison-suffragette-death-derby-1913

JStor

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40972072?seq=1

Biography.com

https://www.biography.com/activist/emmeline-pankhurst

Biography.com

https://www.biography.com/activist/ida-b-wells

Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconstruction_era

Suffragette Stories

https://suffragettestories.omeka.net/bio-constance-lytton

Spartacus Educational

https://spartacus-educational.com/Wlytton.htm